Medically reviewed by L.Saadi, Psychiatry • Updated [September 10, 2025]

Educational information only. If someone may be at risk of harming themselves or others, call or text 988 in the United States for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (24/7), or contact local emergency services.

What Is Bipolar Disorder?

Bipolar disorder is a mental health condition marked by recurring mood episodes, periods of unusually high energy and activity (mania or hypomania) and periods of low mood and energy (depression). These shifts are more intense and longer-lasting than everyday ups and downs and can interfere with work, school, relationships, and daily functioning.

Bipolar isn’t one single pattern. Clinicians recognize several types, each defined by the kind of mood episodes someone has, how long they last, and how much they impair day-to-day life. Effective care usually combines medication, psychotherapy, and practical routines, with treatment tailored to the person and their pattern of episodes.

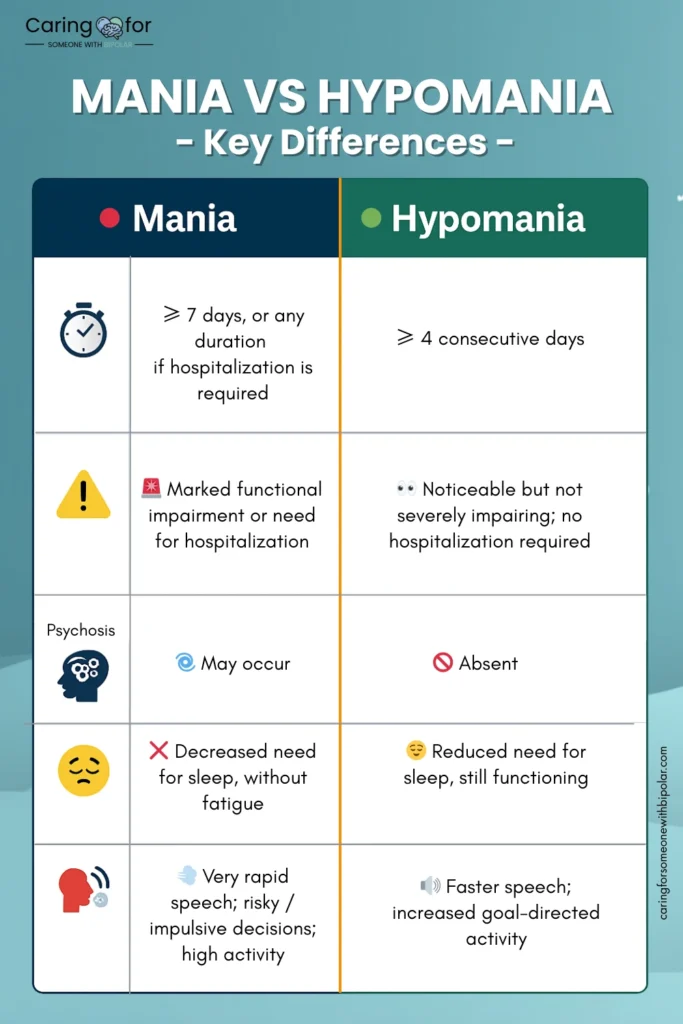

Mania vs. Hypomania

- Duration: Mania typically lasts at least 7 days or requires hospitalization; hypomania lasts at least 4 consecutive days.

- Impairment: Mania causes marked impairment in social/occupational functioning and may include psychosis; hypomania is noticeable but does not cause severe functional impairment or psychosis.

- Common signs (both): Decreased need for sleep, increased activity/goal-directed behavior, rapid speech, grandiosity, risky decisions. (Severity separates mania from hypomania.)

Depressive Episodes

A bipolar depressive episode often includes persistent low mood or loss of interest/pleasure, sleep and appetite changes, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and thoughts of worthlessness or death. Episodes typically last at least two weeks and can be profoundly impairing without care.

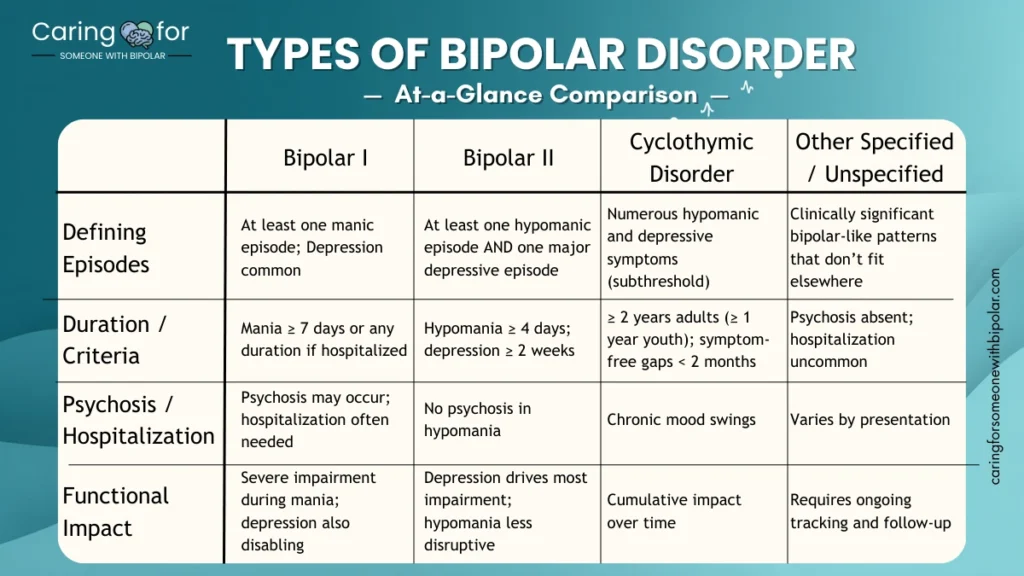

The Main Types of Bipolar Disorder

| Type | Defining mood episodes | Duration / criteria (plain English) | Psychosis / hospitalization | Typical functional impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bipolar I | At least one manic episode; depressive episodes are common but not required for diagnosis | Mania ≥ 7 days or any duration if hospitalized | Psychosis can occur in mania; hospitalization more likely | Marked impairment during mania; depression often significantly impairing |

| Bipolar II | At least one hypomanic episode and one major depressive episode; no history of mania | Hypomania ≥ 4 days; depression ≥ 2 weeks | Psychosis absent in hypomania; hospitalization uncommon for hypomania | Day-to-day impairment driven mainly by depression; hypomania noticeable but less disabling |

| Cyclothymic disorder (Cyclothymia) | Numerous periods of hypomanic symptoms and depressive symptoms that never meet full episode criteria | Symptoms present ≥ 2 years (≥ 1 year in youth), with symptom-free gaps < 2 months | Psychosis absent; hospitalization rare | Chronic, fluctuating mood reactivity; cumulative impact on relationships/work if untreated |

| Other specified / unspecified bipolar and related disorders | Bipolar-like patterns that don’t fit neatly into the three categories (e.g., short-duration hypomania with depression) | Clinician documents clinically significant bipolar features without full DSM-5 criteria | Varies | Important to track carefully and revisit diagnosis over time. |

This table summarizes common clinical descriptions in plain language; individual presentations vary and diagnosis must be made by a qualified clinician.

Bipolar I Disorder

Defining Features & Criteria

Bipolar I requires at least one manic episode. Manic episodes involve a distinctly elevated or irritable mood and unusually high energy/goal-directed behavior, typically lasting a week or more or requiring hospitalization for safety. Depressive episodes frequently occur in Bipolar I, but they aren’t required for the diagnosis. Psychosis may occur during mania.

Everyday Impact & Red Flags for Families

- Sleep drops dramatically for days without feeling tired; activity and plans accelerate.

- Spending sprees, impulsive travel, or risky behavior that’s out of character.

- Speech becomes rapid; ideas jump quickly; confidence turns into grandiosity.

- If there’s loss of reality testing (delusions/hallucinations) or safety concerns, seek urgent care or call 988 in the U.S.

Bipolar II Disorder

Hypomania + Major Depression

Bipolar II features hypomanic episodes (elevated/irritable mood and high energy for ≥4 days) plus major depressive episodes (≥2 weeks). There is no history of mania. Many people with Bipolar II spend more time in depression than hypomania, which often drives the day-to-day burden and risk.

What Loved Ones Should Watch For

- Subtle “upshifts” (reduced sleep need, faster talk, more projects) that don’t obviously disrupt work/school.

- Longer or recurring depressive episodes, including low energy, reduced pleasure, and hopelessness – strong indicators to stay consistent with treatment and follow-up.

Cyclothymic Disorder (Cyclothymia)

Long-Term, Lower-Intensity Mood Swings

Cyclothymia involves numerous periods of hypomanic-like and depressive symptoms that never meet full criteria for hypomania or major depression, continuing for ≥2 years in adults (≥1 year in children/teens), with symptom-free gaps <2 months at a time. It’s often under-recognized but can still disrupt sleep, routines, productivity, and relationships.

Support Tips for Partners & Parents

- Encourage regular sleep and routines; track patterns (mood/sleep logs).

- Watch for escalation into full episodes; keep follow-ups with a clinician.

- Seek help promptly if symptoms intensify or safety concerns arise. Psychiatry

Other Specified & Unspecified Bipolar and Related Disorders

When Symptoms Don’t Fit the “Classic” Types

Some people show clear bipolar features without meeting the exact thresholds (for example, short-duration hypomania with recurrent depression). Clinicians may use “other specified” or “unspecified” to reflect clinically significant mood instability and revisit the diagnosis as patterns evolve. The label still warrants monitoring and, when appropriate, treatment and safety planning.

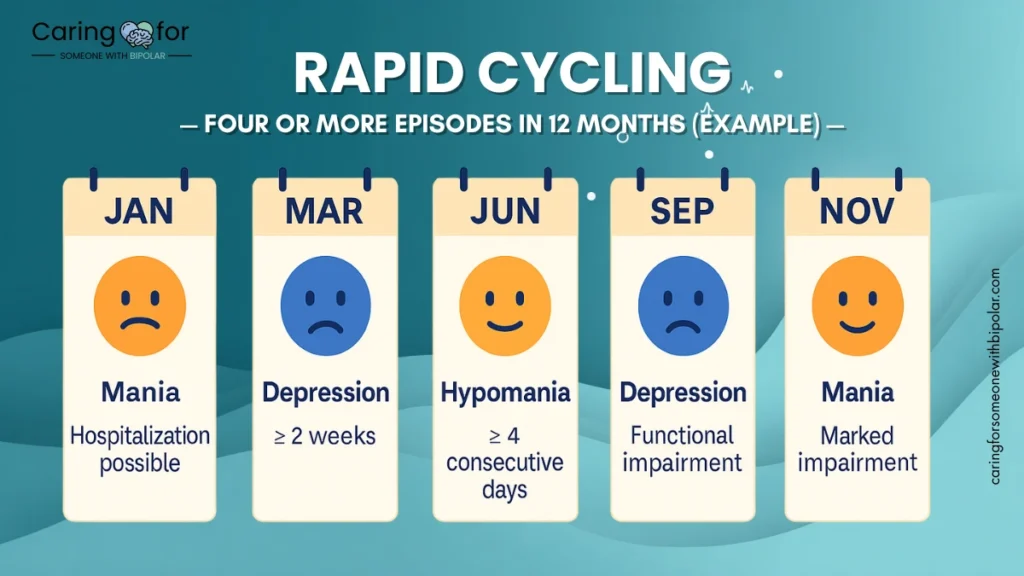

Mixed Features & Rapid Cycling

Why It’s Risky and Hard to Spot

“Mixed features” means symptoms of opposite poles occur together (for example, high energy with despair). This state can raise risk and calls for timely professional assessment; families often notice agitation, severe insomnia, or sudden, disturbing changes in behavior.

Rapid Cycling – What Families Can Do

“Rapid cycling” describes ≥4 mood episodes within 12 months. It’s linked to higher symptom burden; tracking sleep, medication adherence, and triggers (stress, substances) with a clinician can help stabilize patterns over time.

Diagnosis (What to Expect)

Diagnosis relies on a careful clinical interview, medical and psychiatric history, and sometimes collateral information from family/partners. Clinicians use DSM-5 criteria to determine whether episodes meet thresholds for mania, hypomania, or major depression, and to rule out other causes (medical conditions, substances). Journaling and sleep tracking can meaningfully aid the assessment.

Treatment Options (Overview)

Effective treatment for bipolar disorder usually combines medications, psychotherapy, and lifestyle routines. It’s not a one-size-fits-all plan – clinicians adjust care based on episode type, severity, and co-occurring conditions.

Medications

- Mood stabilizers such as lithium remain a cornerstone of treatment. Lithium can reduce mania and lower the risk of suicide when carefully monitored.

- Antipsychotic medications may be prescribed for acute mania or when psychotic features are present.

- Antidepressants are sometimes used but usually in combination with a mood stabilizer to avoid triggering mania.

- Regular bloodwork and follow-ups are essential when medications like lithium or valproate are prescribed.

Psychotherapy

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) helps identify early warning signs, manage stress, and challenge negative thought patterns.

- Family-focused therapy and interpersonal/social rhythm therapy provide structure, strengthen relationships, and stabilize sleep/wake routines.

- Group support can reduce isolation and help families navigate challenges together.

When ECT or TMS Are Considered

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be used when other treatments have not controlled severe depression or mania.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a non-invasive option sometimes considered for treatment-resistant bipolar depression.

Living Well: Routines, Tools & Self-Help

Treatment is most effective when paired with daily habits and self-management tools. Many families find that simple strategies make a big difference.

Sleep, Stress, Exercise, Nutrition

- Keep a consistent sleep schedule – irregular sleep is one of the strongest triggers for episodes.

- Build stress management skills (mindfulness, yoga, prayer, or breathing exercises).

- Prioritize regular physical activity and balanced nutrition.

Practical Tools

- Mood tracking (apps, journals, charts) helps spot early warning signs.

- Daily routines – meals, medication, and bedtime at set times – support stability.

- Involving a trusted support network improves accountability and reduces isolation.

For Teens & Caregivers

- Adolescents may show mood changes differently (irritability, school struggles, risk-taking). Early recognition and family collaboration are crucial.

- Caregivers should practice clear communication and set boundaries while encouraging treatment adherence.

How to Support a Loved One (By Type)

Supporting someone with bipolar disorder requires both knowledge of their diagnosis and practical strategies. Below are caregiver-focused notes tailored by type.

Bipolar I – Crisis Planning & Boundaries

- Recognize mania early (insomnia, grand plans, fast speech).

- Keep an emergency plan with clinicians’ contacts and crisis numbers.

- Protect finances during high-risk periods (joint account oversight, spending agreements).

Bipolar II – Patience with Depression; Subtle Hypomania Signs

- Support through prolonged depression: encourage treatment, maintain connection, reduce isolation.

- Learn to recognize subtle hypomania (reduced sleep, over-scheduling) before it escalates.

Cyclothymia – Long-term Pattern Tracking

- Help track mood fluctuations to spot shifts toward more severe episodes.

- Encourage steady habits: sleep hygiene, daily routines, and stress reduction.

Mixed Features or Rapid Cycling – Structure & Flexibility

- Watch for unusual combinations of energy and despair.

- Support regular medication adherence and track changes with a professional.

- Use structured routines but be flexible for sudden shifts.

When to Seek Urgent Help

- If your loved one shows suicidal thoughts, psychosis, or dangerous behaviors, seek immediate help.

- In the U.S., call or text 988 for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

- If outside the U.S., contact local emergency services or a trusted healthcare provider right away.

FAQs

Sources & Medical Review

- National Institute of Mental Health – Bipolar Disorder

- American Psychiatric Association – What Are Bipolar Disorders?

- Medical News Today – Types of Bipolar Disorder Explained

- NAMI – National Alliance on Mental Illness

- DBSA – Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance

- National Library of Medicine

This article was medically reviewed by [L. Saadi, MD, Psychiatrist] on [September 9, 2025].

Citations include the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), American Psychiatric Association, and other peer-reviewed sources.

Conclusion

Bipolar disorder is not a single condition but a spectrum with several types, each with unique challenges, risks, and treatment approaches. Understanding the differences between Bipolar I, Bipolar II, Cyclothymic Disorder, and Other Specified/Unspecified types helps families and loved ones recognize symptoms sooner, support treatment more effectively, and build strong crisis and self-care plans.

Knowledge alone doesn’t erase the difficulties, but it empowers caregivers to respond with clarity, compassion, and confidence. With the right combination of medical care, therapy, routines, and support, many people living with bipolar disorder lead fulfilling and meaningful lives.

Call-to-Action

Want a practical tool you can use right away?

👉 Download our free Caregiver Checklist (PDF) – a step-by-step guide to recognizing warning signs, building a crisis plan, and caring for yourself while supporting your loved one.

You can also explore related articles: